Why is PM Modi silent about rioting in India?

Elliana James

Possibly due to crowded journalistic headlines on the ongoing war in the Ukraine, acts of “communal violence”, India’s coined term for religious clashes mostly between the Hindu majority and the Muslim minority, in India have been given only sporadic coverage as they escalated since last year and continue into 2022.

An April 20, 2022 article in the Washington Post chronicles a very recent and typical event. A Twitter video posted by India today showed a group of Hindus, marching for hours in a religious procession called "Hanuman" that is part of a Hindu holiday celebrating the birthday of the god Ram. This procession of Hindus, wearing the saffron scarves that signal Hindus nationalism, went in front of a mosque where people were holding evening prayers for Ramadan and waved swords and pistols, shouting pro Hindus slogans and provoking Muslims.

The video posted on Twitter by IndiaToday is narrated with critical commentary by their journalists who decry that so many shotguns are being “brandished in broad daylight” at a holy procession. The narrator asks: “Who gave them permission to carry these?” This video of the incident was taken during the Delhi march but there were similar marches in six other states in India as well. The latest disturbances stayed peaceful in the beginning, but then devolved into rock throwing which required a large force of riot police to disband. Notably absent from the conversation about these events is Narendra Modi, who has been Prime Minister of India since 2014. Modi is the leader of the largest party in the Indian Parliament, the Bharatiya Janata Party, popularly known as the BJP.

Modi also has a Twitter account to which he posts very frequently. With a following of 78.2 million followers, Modi has posted over 32 thousand tweets since 2009. On a typical day he posts about operas and other performances he attends with family and political allies. He also shares his speeches about COVID vaccinations, political rallies and various peaceful religious ceremonies. However, he has so far failed to meaningfully comment on the latest wave of communal violence that has broken out in multiple areas of India.

To better understand why Modi has been so uncharacteristically silent on the topic one can look back in history a couple of decades. He was born and raised in the province of Gujarat on the west coast of India. In 2002 there was a series of riots there that not only caused a possible 2000 deaths in the initial incident but then led to a full year of riotous attacks in the region. At the time Modi was the Chief Minister of Gujarat. He was investigated and cleared in 2012 of culpability of the widespread violence in which mostly Muslim-owned properties were attacked.

In 2013 the Indian Parliament was close to passing a bill for the Prevention of Communal Violence (Access to Justice and Reparations) Bill. Modi sent a strongly worded letter in opposition to the bill. The crux of his argument was that it violated a “state’s rights” concept that would prevent local governments from handling communal violence as they saw fit, based on local conditions. The bill failed to gather the requisite votes and was not passed into law.

As the years have rolled on, Modi has had an increasingly higher political profile as he has led the BJP to victory again and again in the top levels of Indian politics. The BJP is positioned as a pro-Hindu political party. The concept of “Hindutva” which is a shorthand for Hindu nationalism, is strong within the BJP. This core ideology, which emphasizes Hindu identity, pride and cultural continuity, has been part of Indian politics since the founding of the state. However, earlier on, there was a widespread ideological tendency to modernize the caste system as well as religious communities in the name of fairness and equality.

In 2014, the year Modi originally became Prime Minister, the BJP held 336 out of 543 seats in the Lok Sabha which is the lower house of the Parliament of India. This is the main legislative body in the Republic of India. When Modi was re-elected in 2019 with an even stronger mandate from the electorate, the BJP held 356 seats out of 543. During his first five years in power, there have been recurrent and a rising general trend of physical attacks by religious communities against another.

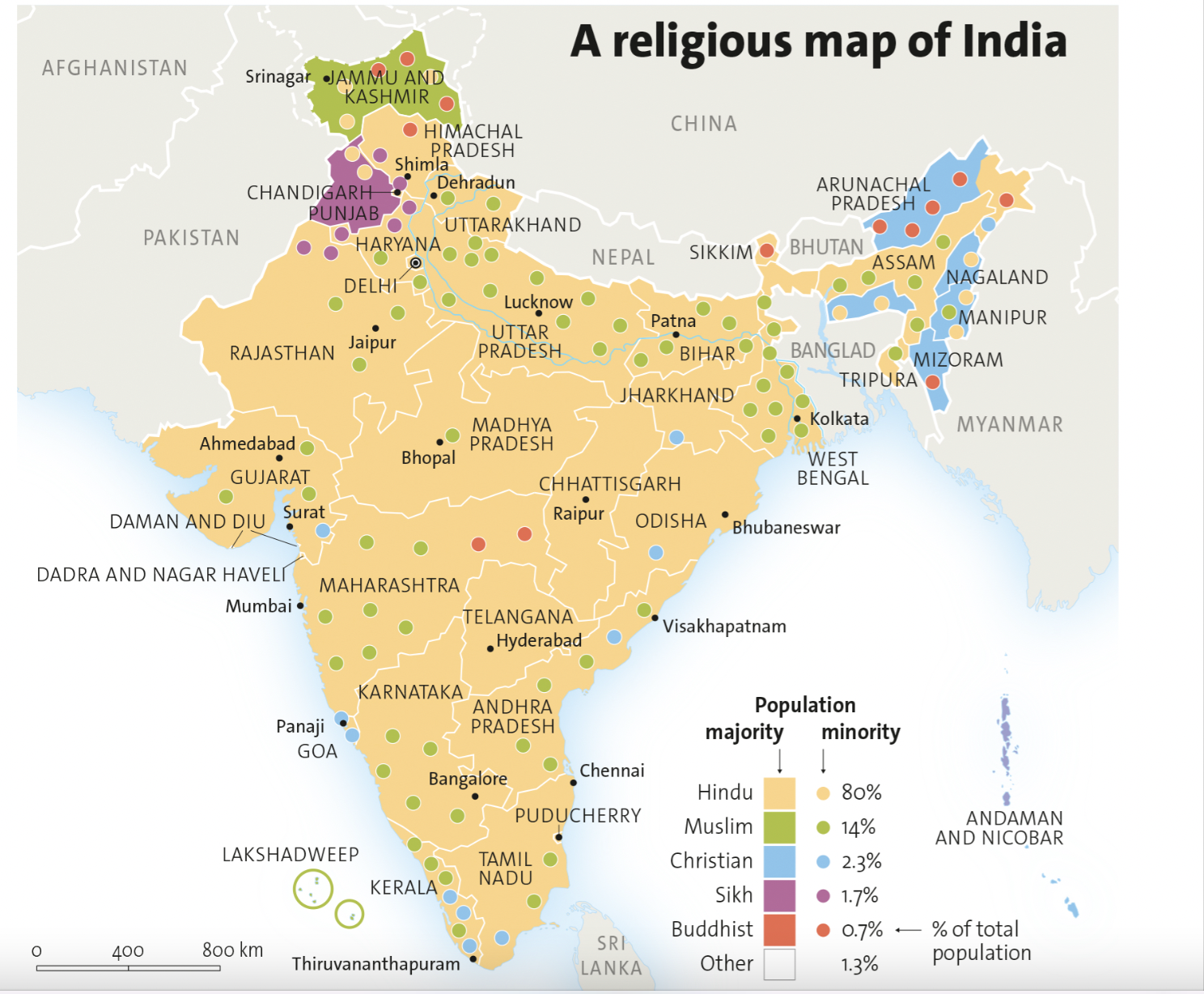

India was technically organized in its constitution as a “Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic” so, although the vast majority of Indians are Hindu, there is no official national religion. India has a population of 1.4 billion people, (2022) or ⅕ths of the world population. Every second a new Indian baby is born. 80% of Indians claim Hinduism as their religion. 13% are Muslim. The remaining 7% of the population is composed of all other religions. With such a large and dynamic population it is inevitable that there is friction and that these differences of opinion haven’t yet been solved.

There have been historical tensions within India on the basis of religion. There is still a strong cultural bias that favors the Hindu majority. This is true despite a 72 year old Constitution which explicitly states that members of minority religions have rights, including rights to gather together to worship, to practice one’s choice of religion and to pay taxes for promotion of whichever religion you choose. Absent from the Constitution are specific remedies for mob violence against others for what, in some other countries, would be called “hate crimes.”

Hate speech, even by prominent civic leaders and religious leaders continues to fan the flames of partisan beliefs. In a 2018 article in the ILI Law Review by Anandita Yadav, Ph.D specializing in hate speech laws published an article on the pros and cons of further criminalization in India of hate speech laws as well as suggesting several other methods of counter messaging via social media and alternative dispute resolution. It is well known that the court system in India is heavily overwhelmed and any use of a more lightweight and timely system to adjudicate lesser grievances could serve as a safety valve against more pernicious trends of violence and dissent.

Although there is an elected President in India, this role is largely ceremonial and the real executive power is the Council of Ministers with the Prime Minister leading them. As in any country there are variations on how involved the citizens would like to be. Here are some of the options outside of Twitter and other social media platforms.

A newly organized (September, 2021) live television channel, Sansad TV is readily available. By law this live channel, which is a Parliamentary channel based in both Houses of Parliament, Lok Sabha (House of the People) and the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) is a must-carry channel that has to be provided via cable, direct-to-home and IPTV networks. Sansad has quite a number of shows however searches of their website for “Muslim” brought up only a few offerings. “Agriculture” as a topic netted 3 pages of news reports to watch. “Economy” brought up a deluge of 9 pages of shows and interviews. The entire Indian population with access to TV or who can watch on the internet will have to decide if they are getting all the news they want or need.

“All Indians Matter” is a website in India started by Ashraf Engineer to bring the conversations that a modern India needs to have to the people. After a 17 year career as a journalist Ashraf decided that traditional news media was not able to stand up to the government pressure and noted the increased costs of actually doing journalism. He therefore decided to provide a platform for this conversation. A typical posting is about the humiliating effect of a ban on hijab wearing in Karnataka. For one thing it is serving to exclude hijab wearing Muslim women from educational opportunities there.

Other political forces in India are also strategizing publicly to take back seats from the BJP. If Tejashwi Yadav, young leader of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD), an Indian socialist political party which has most of its strength in the central east part of India has his way, the opposition parties will focus on wrestling over 200 seats in Parliament away from the BJP in 2024. This coalition consists of all the forces that Modi’s right wing Hindutvaist government is basically ignoring right now. It may appear that Modi, the BJP, and its strongly Hindutva platform might be here to stay and the general population of India is on their side. It is possible that as secure as Modi and his BJP look and feel right now, the tide will turn if enough people in the opposition gather strength to gain more seats in the Parliament in 2024.