Governments in Crisis: Israel and France

Ilan Hulkower

The Israeli government is once more in a state of political crisis. On June 13, 2022, the departure of Member of Knesset Nir Orbach from the anti-Netanyahu governing coalition put the government into the vulnerable position of holding only a minority (in this case only 59 seats out of 120) of seats in parliament. Adding insult to injury, Orbach was also mulling defecting to Benjamin Netanyahu’s Likud party. Remarking upon the severity of these actions, Prime Minister Naftali Bennett commented that “We have a week or two to settle the problems in the coalition…But if we don’t succeed, we won’t be able to continue.” In effect the survival of the government rested upon drawing a member of the opposition coalition into the government (or at least to not vote against the government) and the avoidance of further defections. This was rather a tall order, and it involved a complicated political juggling act to try restoring a semblance of stability to the coalition. In the end, on June 20th, Prime Minister Bennett and Foreign Minister Yair Lapid announced that this gambit had failed and that consequently they were going to dissolve the government. The month of June has not only thrown the Israeli government into a political crisis but threatens to do the same with France given the results of their second round of parliamentary elections. Both countries are examined in this essay.

Coalition crises were not new to this Israeli government. The government itself was borne out of a multiplicity of otherwise divergent ideological camps and interests that aligned against the previous Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu. The main charge against Netanyahu, the longest serving Prime Minister in Israel’s history, was that he had corruptly used his office. The roots of this political alignment against Netanyahu came from the then Attorney General of Israel’s, Avichai Mandelblit, announcement in 2019 that he would be charging Netanyahu with acts of criminal conduct like bribery, fraud and breach of trust. It took the opposition until 2021, however, to mount an effective bid for power against Netanyahu and they only managed to succeed with their scheme to oust Netanyahu by recruiting former allies of his like Bennett who had broken his promises to not seek a rotation government with Yair Lapid and going against his previous comments that no one should be the Prime Minister of the country while commanding a party with under 10 seats. Even when the governing coalition was established, it was a fragile combination of ideologies and interests from onset that rested on total consensus to avoid legislative logjams or defections.

The early on defection by Amichai Chikli, the inability of the government to pass basic legislation, and a declaration by a member of Ra’am that this will not be the last crisis highlighted these fractures. The further defection of Idit Silman, from Yamina, the same right wing religious party that Bennett belongs to, in May put the government and opposition with an equal number of seats. Her defection was over reservations she had about what she saw as leftist and secularization policy that the government was adopting. The temporary resignation of Rinawie Zoabi from the government threatened to leave the government with a minority of seats and vulnerable to a vote of no confidence. Zoabi, who comes from Meretz (a left-wing party in Israel), blamed the right-wing coalition members for the government’s ills. Bennett himself at times was leaked as saying that he thought it was unlikely that the government would serve its full term. The government also has had a major popularity problem with only 30 percent of Israelis approving of Bennett, with Bennett showing that only a quarter of his base were certain to vote for his party in the next election, and with 69 percent of the public disapproving of a scenario where an Arab party is in the next government. It certainly did not help that the government’s tenure was marked by a terror wave of shootings and stabbings in large cities in Israel that were mostly carried out by Israeli Arabs.

Netanyahu’s trials over the corruption charges lodged against him have also not provided the coalition with a sense of vindication. The trials have revealed a shocking level of prosecutorial (and especially police) misconduct, changes in vital witness testimony on material facts, and failed attempts by the state to revise what it charged Netanyahu with. The judges have even voiced criticism with the state. Nevertheless, the coalition has survived these various crises. Given these string of scandals and setbacks, the rebuked prosecution was considering whether to try to convict Netanyahu on an unlisted charge. All these events when translated into the political arena make it more difficult for the coalition to present its case against Netanyahu.

What was unique about the crisis that finally brought down the government is that it threatened to leave the government vulnerable to a vote of no confidence as it only has a minority of seats in parliament and that various entire factions of the coalition were reported as talking or considering the possibility of talking with Netanyahu about jumping ship. Mansour Abbas, the head of the Islamist Ra’am party, recently commented that he would not rule out partnering with Netanyahu. Old protégés of Netanyahu were also reported as testing the waters over defecting from the coalition (although they deny it). Gideon Sa’ar was reportedly engaging in deep discussions over potential ministerial portfolios of a government with Netanyahu. Bennett himself was accused by the press of weighing an alternative government with Netanyahu. With the announcement of the intent to dissolve the government, it remains to be seen whether a new election will be necessary (which is the most likely option) or whether there is time for Netanyahu or someone else to, through parliamentary maneuvers, form an alternative government.

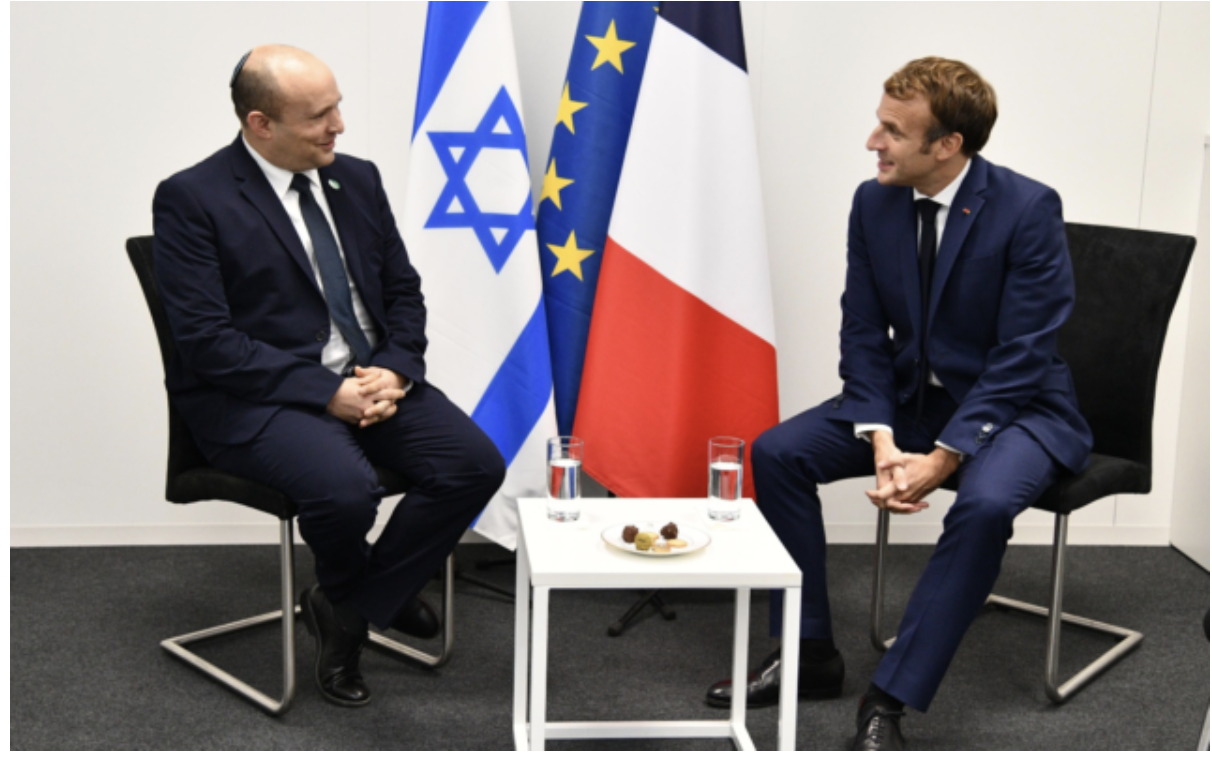

France is another state whose government is experiencing a crisis. The failure of the President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist Ensemble coalition to secure a governing parliamentary majority in the June 19th elections for the National Assembly threatens the government’s legislative agenda. While Macron, who won re-election with 58.2 percent of the vote against Le Pen, is the first French president since Jacques Chirac in 2002 to win re-election, the reason for his victory was not so much a triumph of the French center and its policies or even enthusiasm for Macron, who remains unpopular. His victory boiled down to an adverse reaction by the older generation and by the Left to the prospect of a Le Pen presidency. The decimation of Ensemble from 347 seats to 245 seats, which was below the 289 seat threshold for a governing majority, and the rise of non-establishmentarian opposition parties as evidenced by Jean Luc Melenchon’s NUPES coalition going from 58 seats to 131 seats and Raassemblement National, the party of Marine Le Pen, going from 7 seats to 89 seats, should be seen as a warning sign to the center that they need to reform their policies to better appeal to the French electorate, lest they risk total collapse. While the French center is not dead and commands the most seats in parliament, it is certainly not the force it was in 2017 when it won both the presidency and the parliament by large margins. The great irony in Macron’s loss of his majority in the National Assembly is that Macron himself has contributed to the decline of the French center by combining the fortunes of center right and center left together into one party. These political forces, once represented by the Socialist Party and Union for a Popular Movement party, had previously been the stabilizing power behind the French Fifth Republic that was founded by De Gaulle. In doing so, the opposition was free to create a distinct identity of its own that was at a distance from the centrist coalition and evidently these largely anti-neoliberal identities have caught on with a large swath of the public.

Macron’s options at the present time are to govern with legislative gridlock, call for new elections, or try to form a working coalition with an erstwhile opposition party by adjusting his agenda. Forming a working agreement with the conservative Les Republicains, a once mainstream political party that itself is experiencing declining fortunes in recent elections, would theoretically be the easiest route for Macron but the head of the party said that they would stay in the opposition. Macron could try to form a deal with Jean Luc Melenchon by offering him the premiership, a post Melenchon has stated he desires. Such a pact, however, would involve major compromises over domestic and possibly even foreign policy stances by Macron. The fact that Melenchon’s parliamentary coalition is itself somewhat fragile may also present obstacles to reaching a durable understanding given that certain parties to the left coalition could abandon the government any time they feel that their sub-faction’s demands are not being satisfactorily met. Additionally, given France’s present economic woes such a union with the anti-establishment left may only exacerbate these problems. For instance, one of the anti-establishment left’s planks of spending more government money would not be wise given the inflation crisis gripping the country. Hence even if Macron can pull off an alliance with Melenchon that would be politically beneficial to him such an alliance may not be beneficial to the country. If Macron should try to sway Le Pen’s political party to his side, this would not only risk major policy compromises but also ideological repudiation from the center that are much more antagonistic toward Le Pen than Melenchon. It therefore remains to be seen if Macron can form a stable government in his second term. If he cannot then France risks legislative deadlocks becoming a feature to its politics and his domestic and foreign agenda risk being largely stymied.